Some reported sightings

Prudence Hemming

The project explores the lived experience of three generations of Adelaide women who were victims of sexual violence between 1971 and 2040. Historical reports capable of being transmitted across time form the basis of the research.

The literary trove of an Adelaide family discovered in a room on the ninth floor of a building on North Terrace, Adelaide, is the work’s starting place. Here, the archival remains are being investigated by the researcher, Adele Wunderlich, an expert in recovering manuscripts damaged by time, natural disasters, or catastrophic events.

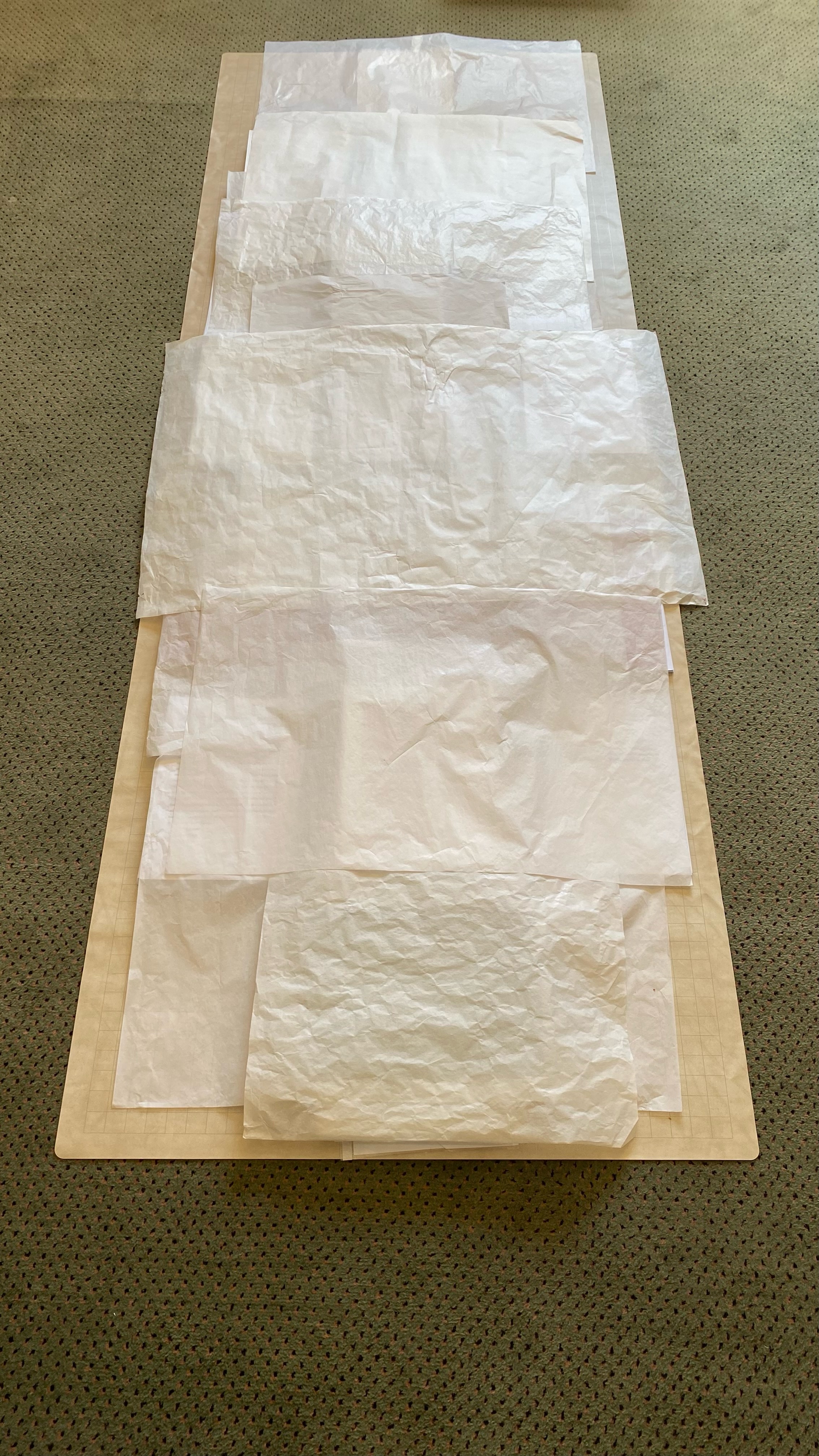

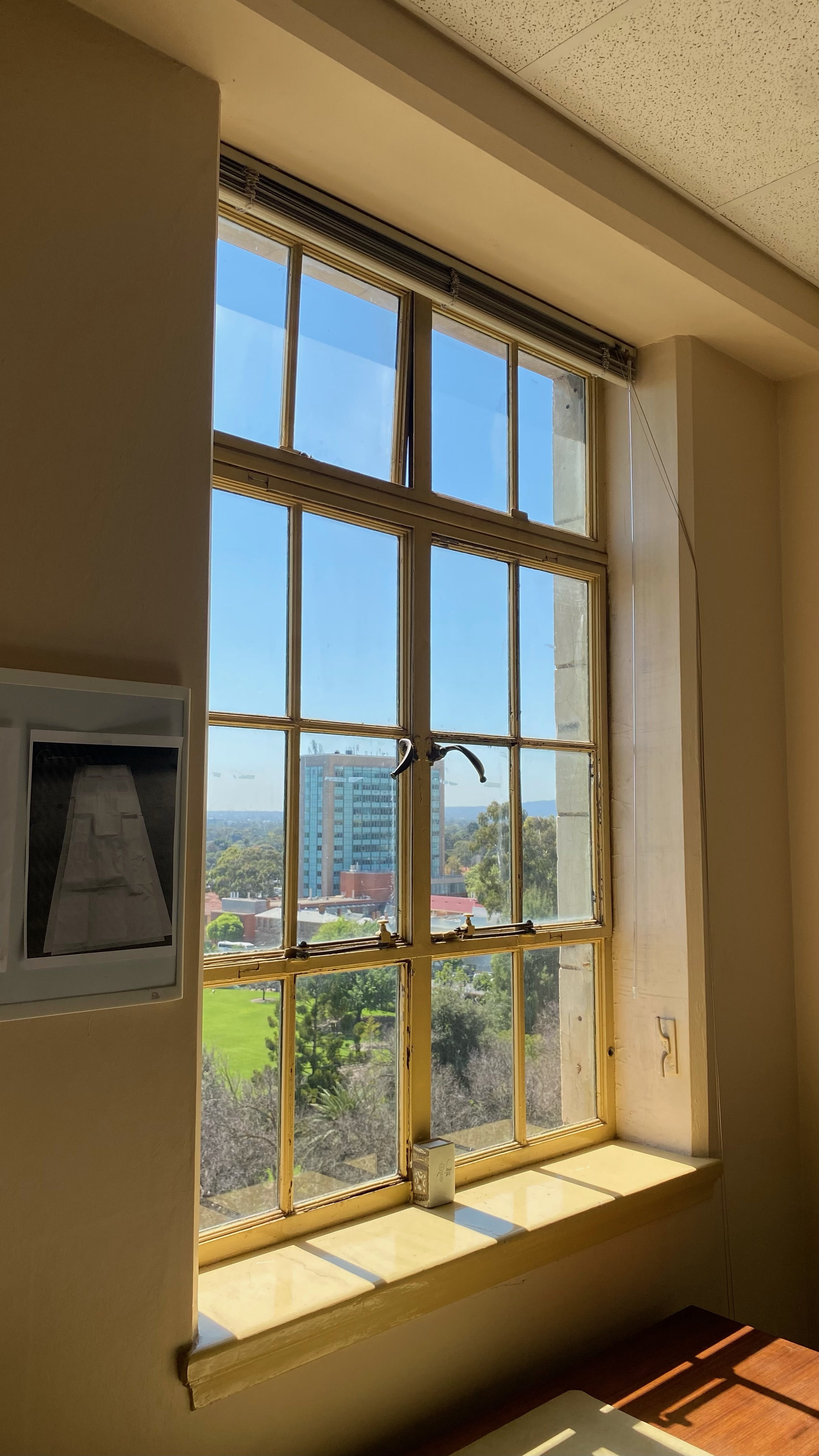

I met with Adele in the space to discuss her approach. Piles of stacked papers lay spread across the floor. From the northern window, a blue-sky view of Adelaide extends as far as the eye can see. A typical scene in direct line of sight shows a statue Dame Roma Mitchell, South Australia’s first female governor, sitting under the ash trees outside Government House, book in hand. Only ten steps to her left, Adelaide’s replica of Venus covers herself with a drape.

Adele apologised for the lack of chairs. Standing was the only option. About to ask permission to record the interview, she interrupted my thoughts.

No recordings, please. The project is at a crucial stage.

I was curious to learn more about this find. The archival material surrounding us, with the sight of Adele wearing what could have been either a white lab coat or Gucci Ouverture set the scene. I felt as if I were walking on stage.

By the way, call me Wunderlich. I don’t like being called by my first name.

Looking more preoccupied than evasive, she continued.

These stories, journals, and letters have been handed down to us by three generations of women in an Adelaide family. For ninety years, the archive continued to expand. Meanwhile, the women disappeared. In most cases, the name of the writer was erased. Now we know each woman’s name. The DNA from successive handwriting on the paper was easily matched to the paper's age. The types of ink were also used for identification.

Wunderlich moved around the edges of the room, sidestepping the paper mounds.

Many of the pages are stuck together, impossible to separate. Others, partially preserved, are discoloured and stained with mouse-eaten corners.

I later realised how in this particular line of enquiry, material states of decomposition are the fundamental rule, like epigenesis in reverse. Texts can easily become unreadable.

Wunderlich’s method enables her to scan the manuscripts without opening or turning any pages. Using non-invasive, micro-CT scanning, she has digitised the cursive and typed writing. Now, she reads the pages in a continuous scroll projected onto a wall in the room.

I had to listen carefully. Wunderlich started speaking quickly, her pitch and tone grew higher with each explanation. Again, she had this knack of being able to intercept my thoughts. ‘Strange,’ I heard her interject.

Quite the opposite. Not strange. Commonplace. This goes hand in hand with covering up the perpetrators as well as the forms of violence inflicted on women and children. What's unusual is to find yourself confronting by proxy such deeply personal accounts. Sexual assault, violence, and harassment are part of everyday life. Meeting these women in such harrowing circumstances came without warning.

Encounters like this are always a first time. Like the women in the past, she had no prior experience, but she has names for the crimes. They had none.

This brought us to the significance of her current location. For a long time, this was the tallest building in Adelaide, renowned for its 360-degree panoramic view.

After The Great Depression, it was known as ‘The Jumpers’ in memory of those who killed themselves. Many of the well-recognised structures dotted below haven’t changed since 1932.

Wunderlich maintains they all carry the weight of evidence.

Adelaide and its buildings are crucial to understanding the annals under investigation. Looking down from here, the places we frequent look like they were dropped from another planet. The crimes men committed lie hidden within their walls. Names on walls have been digitised. The flagstones of the footpaths they walked have been replaced. The list goes on.

Wunderlich sees the archive and its location as camouflage, the women’s only way of staying alive.

These atrocities were covered up. It wasn’t until the end of my reading that the story hit me like a bolt of lightning. The sites of these crimes were staring me in the face. Look out the window. Hear the sound of their steps along the path. Feel those turning faces, their smells, the sounds echoing.

I didn’t know whether to rebel or cry. Wunderlich talked more to herself than to me. By now, I was speechless, rendered dumbstruck.

These records send us their life-giving attention. It must have been very lonely—their whole lives.

Wunderlich has yet to determine the next step.

This project will report on how transmissions travel across time. How do we receive the messages of these women when they cannot speak or have been silenced? There are more questions than answers. This state has to be experienced directly. If not lived through, then experienced through attunement to affect. In these cases, the perpetrators have all died. All of the women have passed away. I believe the inheritance from this violence is an impersonal force always ready to repeat, poised to infiltrate future generations. This research will demonstrate how such deathly destruction feeds on our life-giving capacities and how we can refuse it entry. The treasure is contained in this life-affirming trove of bodily images, touch, and dialogue with others. When I scanned the page, and held the objects, I felt the impact of this contact. After a century of isolation, here is the opportunity to change the course of our lives. Does this sound like giving birth? It is.

‘Can walls speak?’ I ask.

Yes. They also breathe, touch, and sense the atmosphere, alerting us to be sensitive to the vibrations flowing around and between people. When we listen deeply to the walls, we are listening to our senses, and by putting this into words, anything can happen. Remember that, Prudence.

When I walked back onto North Terrace, everything looked different. Things were bright, not strange.