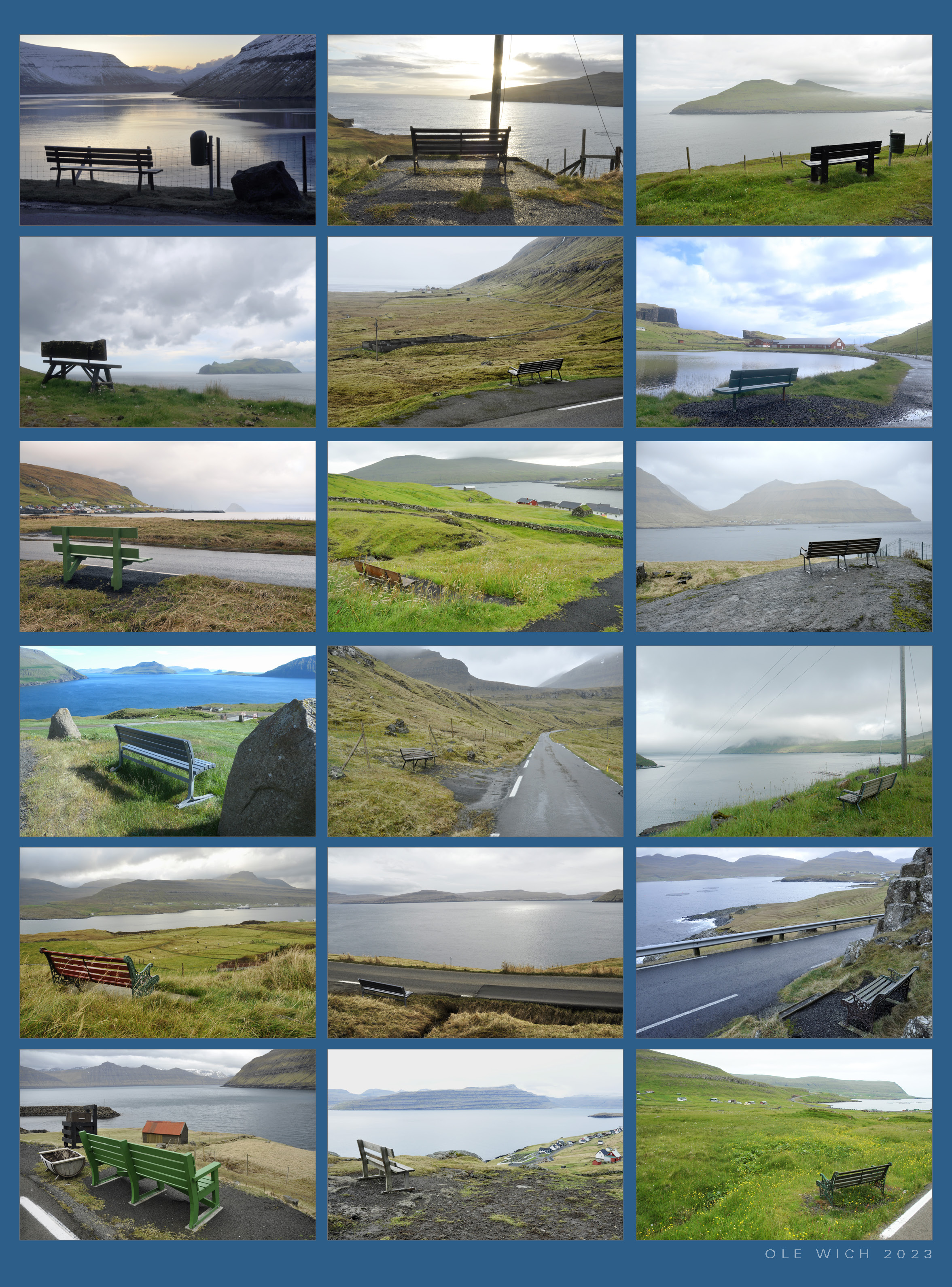

Some benches with a view

Ole Wich

Artificial mountains of culture stack up in the island landscapes. From the piles of colorful pamphlets and travel books describing the Faroe Islands, voluminous words evaporate, constantly. The lines of letters swirl out in thick spirals, rising up, gathering in heavy clouds covering the mountains, inlets, and islets in front of eyes that read.

Are these truthful words or a covert cover-up? The answer lies in the cloud-covered facts. Take now the idea of untouched nature so commonly applied to the Faroe Islands. It is a lie. The fact is that every inch of Faroese soil containing plants and accessible to the numerous sheep roaming the islands is at risk of being bitten down to its roots and exposed to the rough Atlantic elements and then washed away or blown into the ocean.

But how did these voluminous descriptions of the Faroe Islands appear in the first place? Travel literature published by foreigners through centuries was the first step. It continued later when local literature emerged in Faroese language. Finally, the tourist industry took over. Along with the streams of words came the visual descriptions of the Faroe Islands through the traditions of painting and illustration, mostly landscape images. A scenic depiction is a representation on an erected, framed rectangle in front of the painter. These depictions affect perceptions of Faroese nature and have altered the local population’s view of themselves, too. In this portrayal, nature is placed far away.

In the narrow verge between Faroese roads, fields, and buildings, at the edges of the heavily used areas altered by humans, sprout peculiar products of natural interest: some benches with a view. A bench is a sitting device that forces the body into a seated position. The eyes are directed into the landscape scenario, a picture imbued desperately with a striving for creating meaning. The benches place artificial frames around nature. Apparently, you are obliged to stop, sit down, and see the surroundings as and within a picture, a panorama. Forced to see nature at a distance, these roadside constructions are absurdly spread across the surface of the Faroes. However, it is extremely rare to see the benches being used. Few ever sit on them.

The human experience of Faroese nature was originally a complete bodily experience involving all the senses. Previously, before the dominance of thinking and vision through literature born from the visual arts over a more embodied perception and experience of nature, the local population largely explored and recognised the Faroese landscape visceral and through being present. People walked, penetrated the countryside, and observed the forms and surfaces. They placed their own words on top of the landscape, creating placenames that connected their daily lives to the cliffs, stones, and the soil. They were still close to the realities of nature.

Through the emergence of literary descriptions, the art of painting, and the later massive production of landscape descriptions, behind the clouds of words, and in the projections of the landscape on a vertical plane, the immediate experience diminished. The remoteness in ideas about nature existed in contrast to the closeness in the body and direct connections to natural phenomena. Distances were put between people and nature.

When the actual need among people for benches is small, what, then, is the philosophy behind the arrangement of the vacant infrastructure? A lot of resources are spent by municipalities on some benches with a view, despite their limited use. Apparently, these authorities consider the benches necessary. But why? Perhaps they are signifiers from the administration to the public to manifest some sort of nature awareness. In reality, though, the benches exist as meaningless monuments over a view of nature that is outdated and increasingly harmful to the interaction between humans and nature.

The real issues in nature conservation and restoration cannot be seen from a distance as a panorama. These representations must consist of a detailed look at all the small parts in the complicated and numerous interactions in the natural world, of which the Faroese snippet, from the top to the smallest part, is one of the most exquisite on the planet.