Some history

Adrian Young

A specter haunts history, or at least it should. History writing, after all, relies on the dead. Historians use the lives of those who lived and died before we were born to populate our stories. We query the dead. We speak for them, about them, of them. We question their judgments, muse on their silences, read their words, disentangle their contexts and relationships, and put them in their place. Above all, we drag them from the uncertain rest of the past into violent reanimation in the present, making them live again to tell our stories.

In Northwest Madagascar, in the port city of Mahajanga, the descendents of the Sakalava kings sometimes meet spiritual mediums at the shines of their ancestors to engage in “tantara”, the formal tradition of history. The mediums invite in the spirits of the dead to possess their bodies, not exorcisim but its reverse, adorcism. The ghosts of historical figures long dead inhabit the living, each representing diverse historical moments. Anthropologist Michael Lambek describes it as an act of dialogue between different eras, including our own present:

The spirits juxtapose distinct historical epochs. The juxtaposition is a part of their very constitution, for they emerge through contrasting signifiers of comportment, clothing, furniture, drink, dialect, and so on. What is still more significant, the space of performance enables the simultaneous display of successive temporalities. Sakalava history is thus additive in that, in principle, later generations do not displace earlier ones but perdure alongside them. Moreover, and this is a central point, the conjunction of temporalities, including the present, allows each period to serve as a locus of commentary on the others.1

History—tantara—is thus not, or at least not only, an act in which the present calls the past to account. The opposite is also true, as the present is made to answer to the past. The dead are reanimated, but they also have some questions for the living, who had better have answers.

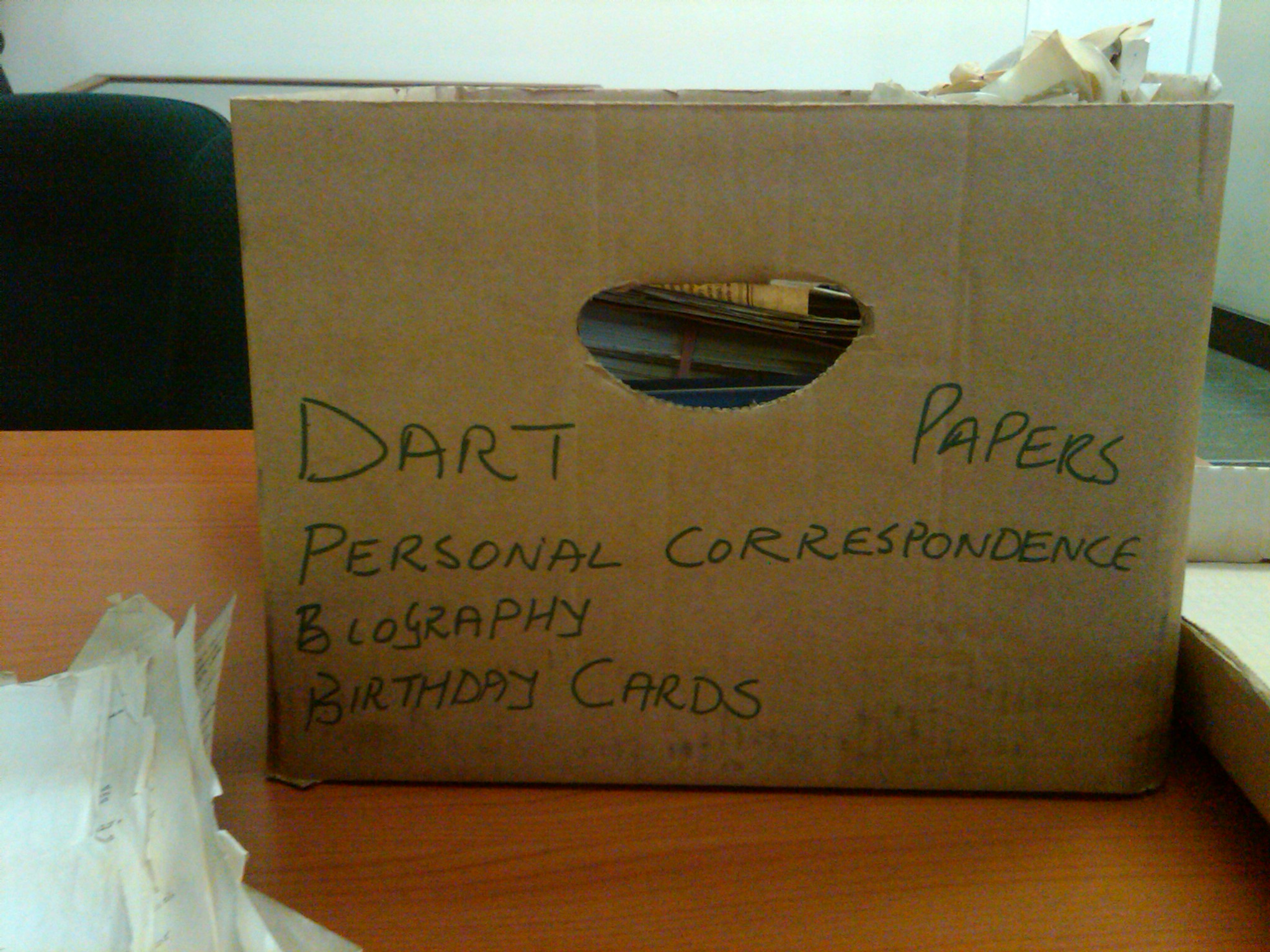

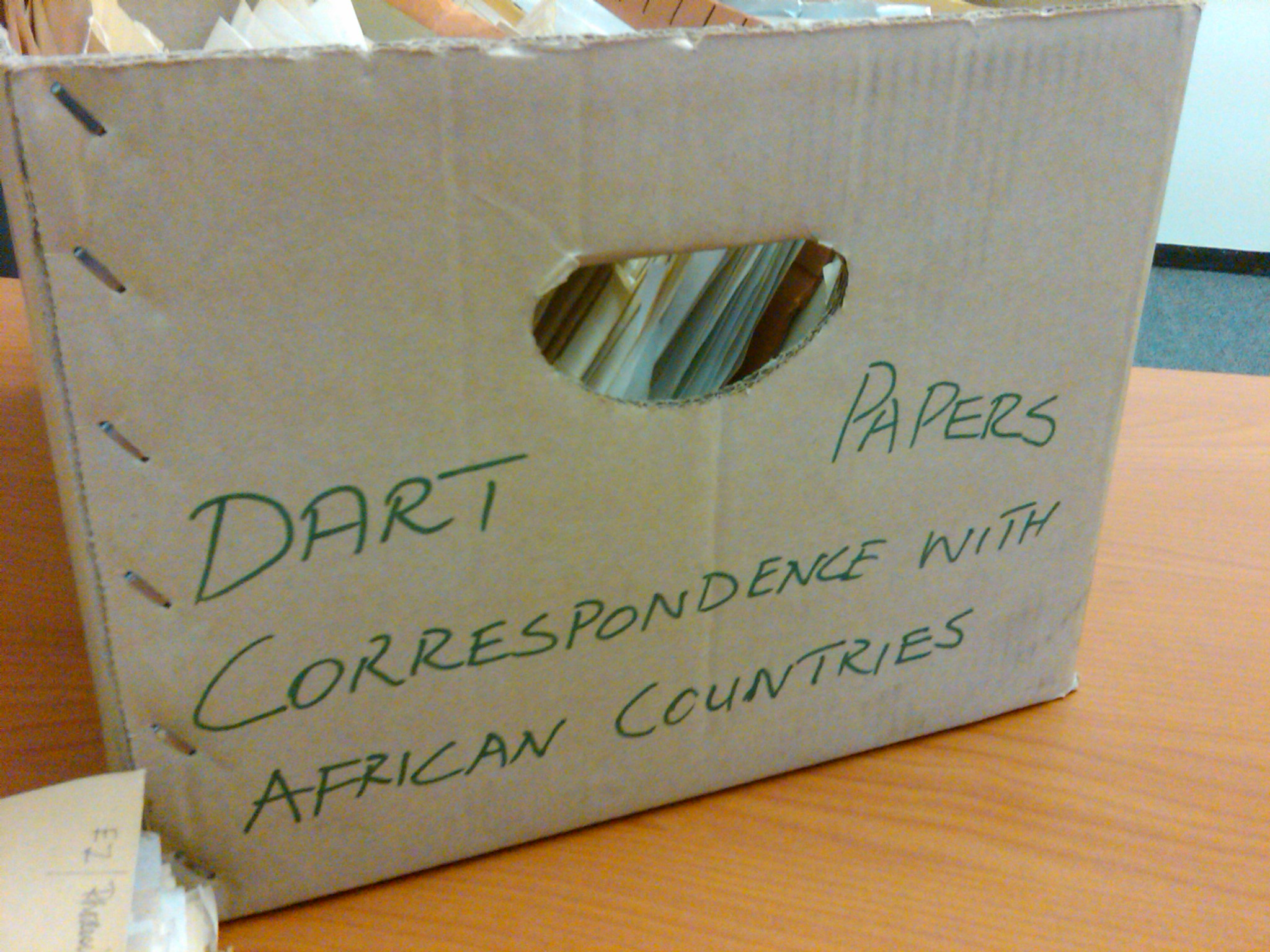

I sift through the broken glass and papers that lie atop each other in a cardboard packing box. It is 2007 and I am in the special collections of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. It is the summer between my junior and senior years at the Ohio State University. I have never been to an archive before. I have never been to Africa before. But here I am, gently, lightly, snooping through a dead man’s things. Raymond Dart was an anthropologist, most famous for finding the “Taung Child”, the skull of a human ancestor fossil, an australopithicushe ‘discovered’ in the mines that made some South Africans very rich and others very poor. Or, at least, he is famous for having identified a fossil someone else, one of those poor minors, found in the earth.

In my thesis, Raymond Dart will become an illustration of the ways anthropologists relied on the often anonymous, indigenous labor of Africans to produce their discoveries, people whose lives and experiences are, for historians, often lost forever. I will mention, offhandedly, that he later testified in the hearings of race boards in the apartheid state, adjudicating who was white and who was black. I will not mention that in the archive of the University of the Witwatersrand, the last relics of his life were swept unceremoniously into a large cardboard box upon his death, never to be opened again until this moment. I will not mention that the glass and frames that held photos of his family had shattered, and that shards and glass dust had worked their way through his disorganised papers, cutting my fingers. I will not mention that in those letters and files, I found disappointments at rejections, celebrations of successes, that I found love notes.

There is a boundary that separates the present from the past. Its borders are uncertain, and not universally defined. I am not sure where that boundary begins or ends, myself, but I know that its only clearly defined edge is death. There is a slowly cresting wave, forever rolling and unfurling, that runs unceasing through time. On one side are the living, and on the other, the dead. Once no one lives to remember something, surely the present has surrendered itself fully to the past. Then, inarguably, historians can proceed with their work.

But what do we owe the dead, whose lives and existence define and constitute, in so many ways, the substance of our projects, the souls that animate our writing? Perhaps more than we let on. Pacific historian and anthropologist Chris Ballard has argued that we need to look beyond our singular, western conception of historicity—of how we do history, of what makes a thing historical, about what separates or unites present and past—and embrace other historicities.2 Europe, at least from the Enlightenment, has treated the dead as gone, and their relics as so much data to be analysed as we please. Other historicities are less cavalier. I suggest that we should pause, and ask what, if anything, we might owe the dead in return for the right to make them our actors and puppets. How much of their human selves belong in our own stories, if we’re going to engage in such necromancy in the first place? Which lives should be reanimated, and which should be allowed to rest? And, when we wring drama from their suffering, whom does it serve?

1 Michael Lambek, “The Sakalava Poiesis of History: Realizing the Past Through Spirit Possession in Madagascar,” American Ethnologist 25, no. 2 (1998): 106–27, 108; see also Michael Lambek, “On Being Present to History: Historicity and Brigand Spirits in Madagascar,” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6, no. 1 (June 2016): 317–41.

2 Chris Ballard, “Oceanic Historicities,” The Contemporary Pacific, 26, no. 1 (2014): 96–124.