Ole Wich

Oceans are fluid, endless, turbulent. Sea masses drift around without anchors. In some places, movement is prevented where sea beds rise and penetrate the surface. Visible landmasses materialise as continents and some islands. Our perception of these significant breaks in the monotony of the floating oceans change how we pose land and sea, self and world. I seek out and observe a single uninhabited monolith in the North Atlantic, obtain data about this island, and apply selected theoretical systems. Through this phenomenological method, I present possibilities for creating a perception of the remarkable phenomenon, Lítla Dímun.

1

1Lítla Dímun is the smallest of the Faroe Islands. Sail past the island and you will see from the windswept summit the uninhabited basalt flats spread out in all directions stacked horizontally. The geology cuts into jagged slopes that drop to the sea surface. There, the solid rock is met by the eternal pounding of waves, relentlessly gnawing into the island massif and breaking the rock into vertical wound surfaces. The isle is an amorphous lump of rock rising from stormy fluid, the island’s shape being eroded and slowly changing over eons. Ever undeterred, Lítla Dímun breaks up through the ocean in the middle of the vast meaninglessness of the infinite, a solid statement we can call island.

2

2The islands appears in the distance. The relationship between landmass and sea is used by shipmasters to navigate the vast ocean. In the North Atlantic between Norway, Scotland, and Iceland, such sights puncture the wavy water. These eighteen basalt massifs comprise the Faroe Islands. On the markers shown, the islands of Suðuroy, Lítla Dímun, and Stóra Dímun were photographed on a reconnaissance voyage in 1898. The cruiser, Heimdal, was north of Lítla Dímun and recorded the location of the line of sight where the silhouettes of Suðuroy and Lítla Dímun just come apart. If you see another landmark at the same time, you have established a position.

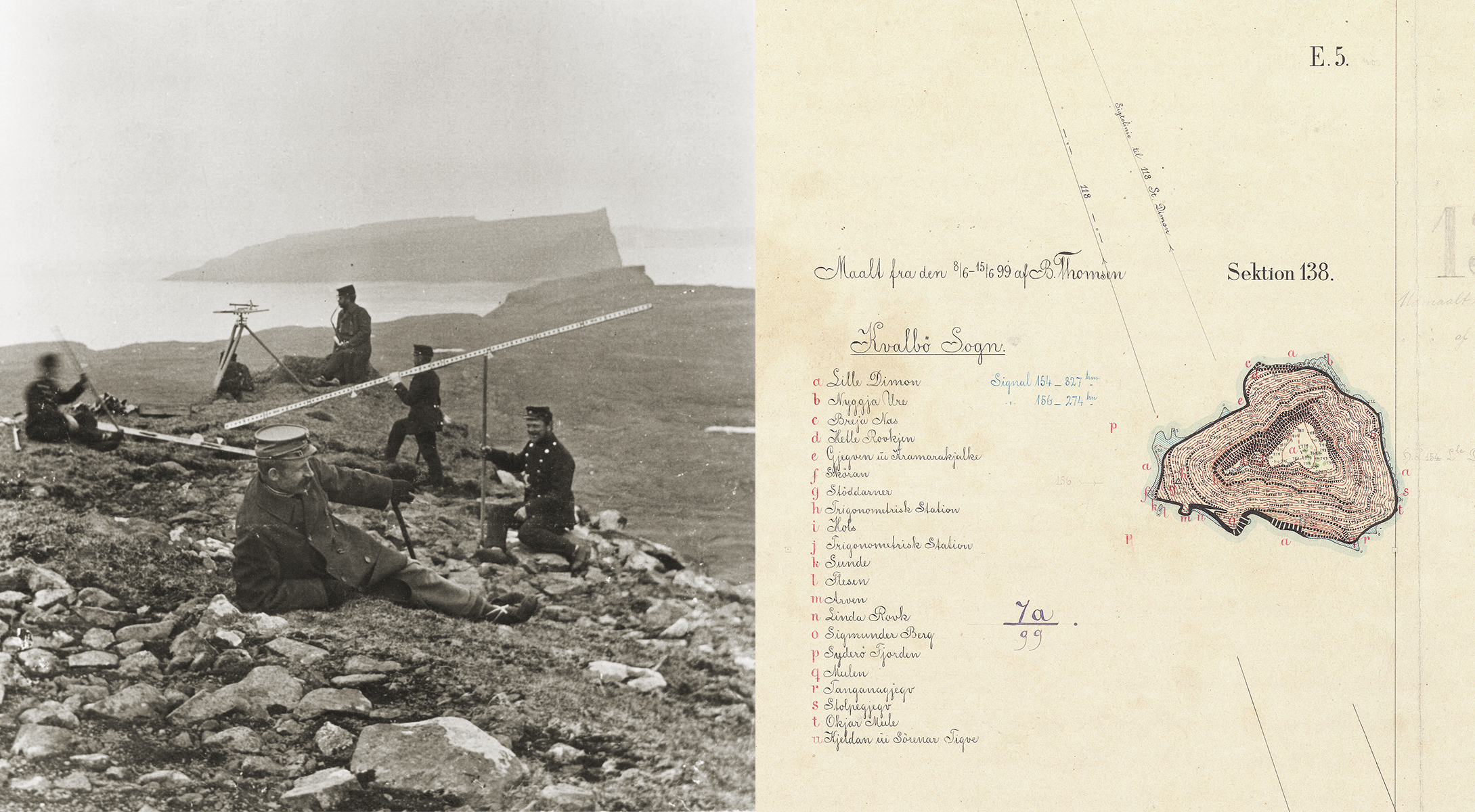

You can place yourself in the island landscape and lay down a system of sight lines over the island’s ruffled shape. You set up a plane table with a telescopic alidade in a known position and at a known height. Your assistant places a levelling rod at selected points on the island’s surface. You read the horizontal angle, the vertical angle, and the distance to your position. You record the levelling rod’s position. The collected data are drawn in a two-dimensional representation on paper, a plane table survey map. When all your careful observations come together, you are able to describe the shape of the island.

3

3Place a plane table on top of Lítla Dímun. Draw sight lines to landmarks around the island and on the globe. Calculate the position of the measuring table and the height above the water’s surface. On the plane table map, the measuring team recorded selected position coordinates and heights on the surface of the island: “During the measurement, the location and height of so many points are determined that the terrain with the objects located on the same can be completely drawn on the table” (Sand, M.J. 1895–1896).

The result is two-dimensional visual representations at a reduced scale of 1:20000, where the third dimension—height—is indicated by numbers. Connect the numbers with dashed height curves, indicate the steepest places by Lehman slope hachures. All these data describe the shape of the island. Collect a list of names from the island’s residents and locate their position on the plane table map in red letters.

4

5

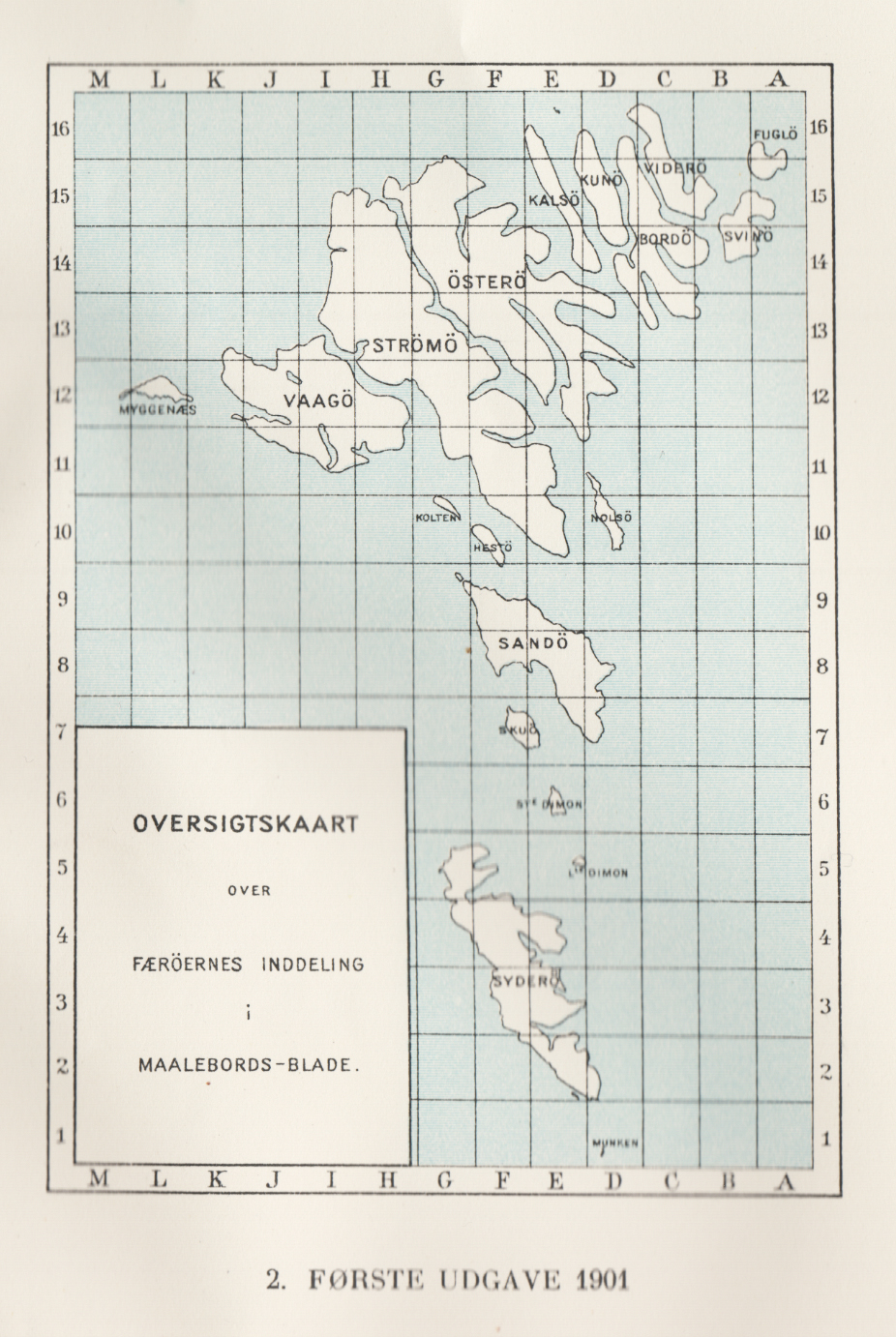

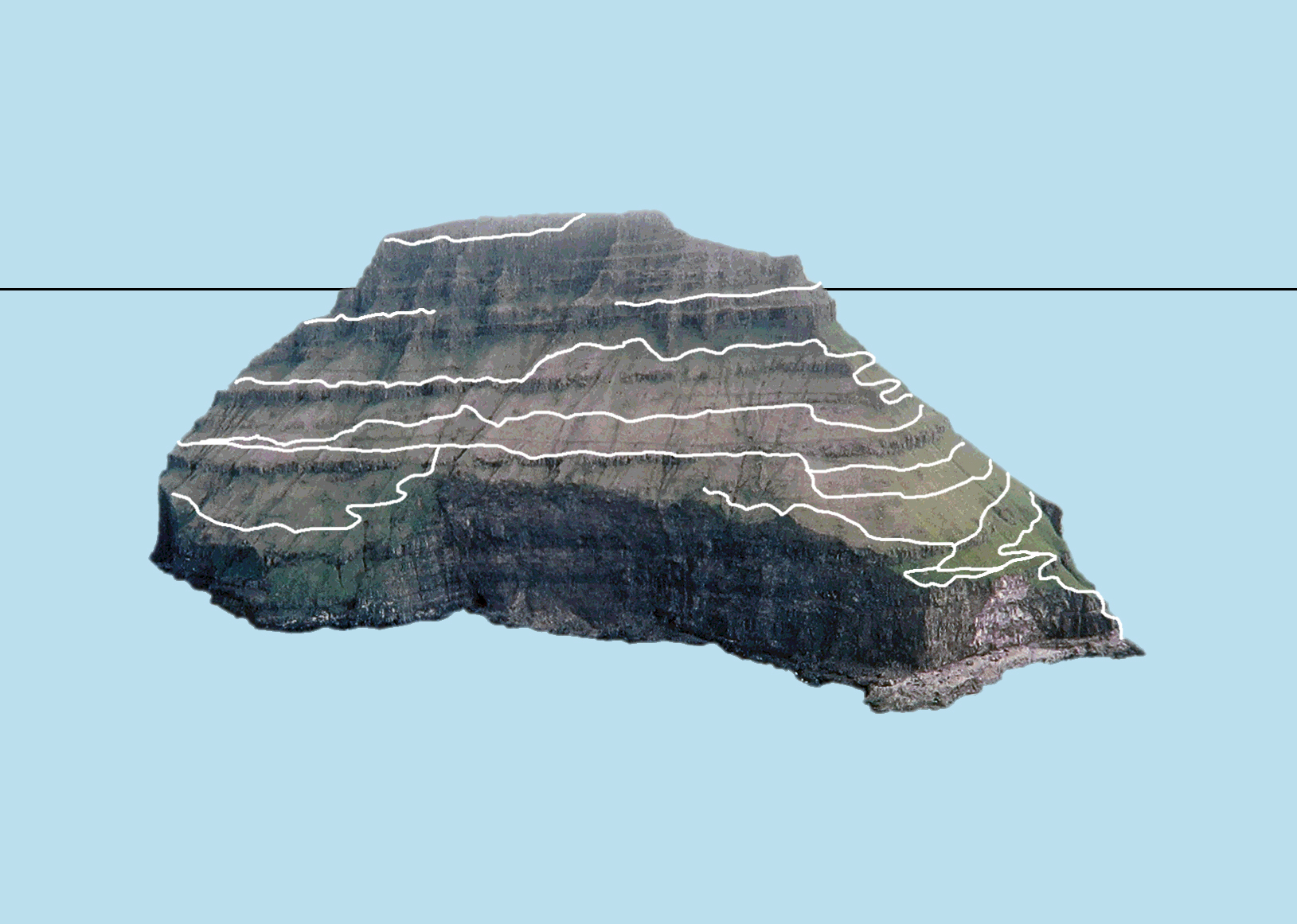

5When the cartographer stepped aboard the airplane and saw the landscape from the air, it gave easier access to data about the surface of the island. Since 1958, the archipelago has been regularly photographed from the air. Maps project the shape of the island on a horizontal surface, but can the projections of Lítla Dímun on a flat paper give better insight into the actual shape and nature of the island? It is difficult to perceive the island’s peaks and sloping sides in two dimensions. There are surely other methods.

6

6 7

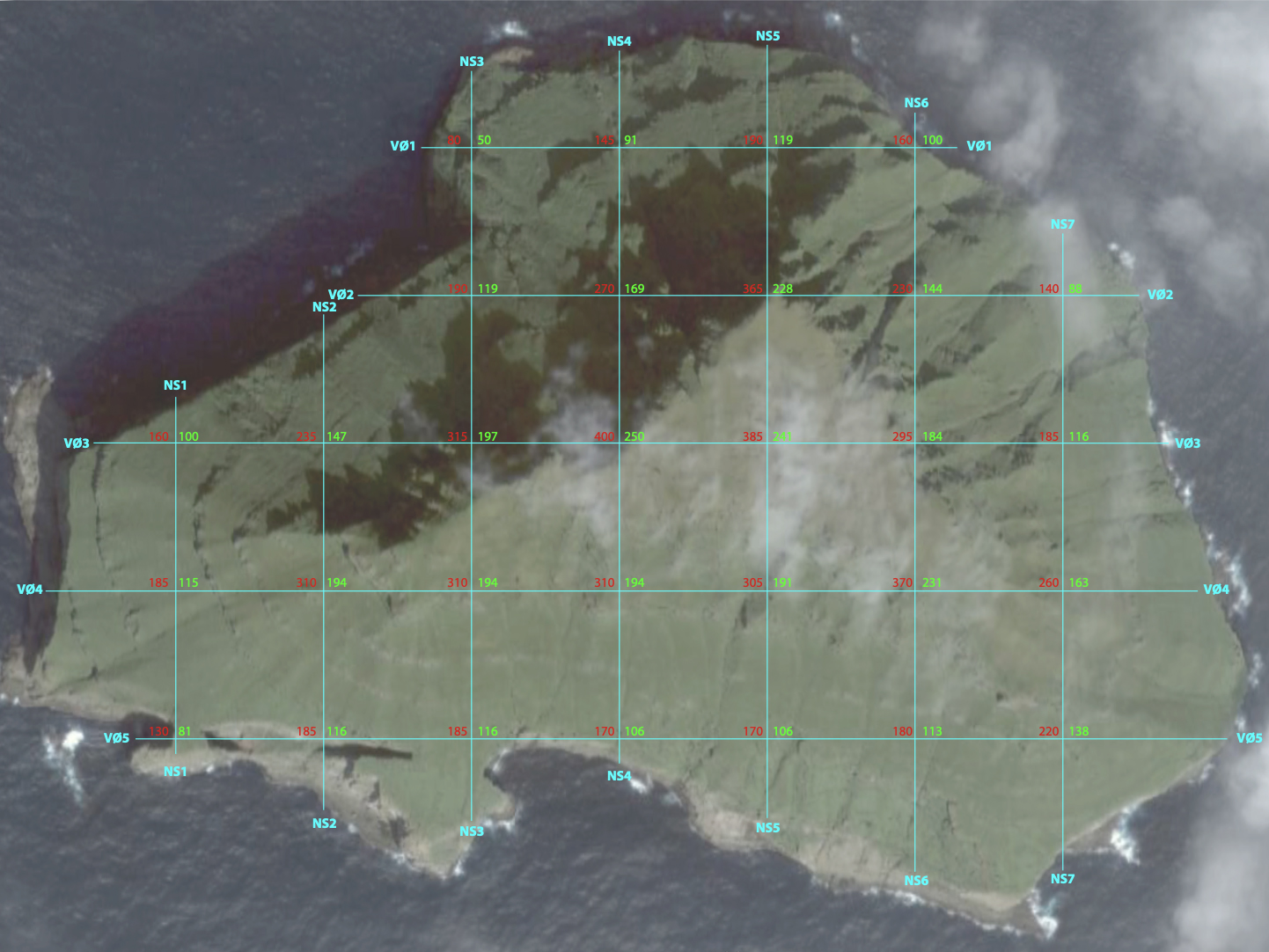

7On the maps, the cartographer has drawn the meridians north-south and east-west. The lines are fictions added in order to place the island's data on the two-dimensional plane. I place my own fictitious square grid of latitude and longitude over the surface of the landscape on a aerial projection of the island. I record the heights of the island where the lines cross. The coordinates of the square grid and the associated elevations, thirty sets of three numbers, give an idea of the shape of the island. This method is only a rough representation of the physical conditions.

8

8Now, imagine that these fictitious lines running across the surface of the sea towards the island are deflected by the rock massif upwards and following the shape of the island along the surface. The lines continue over the sea on the other side of the island. By physically imitating this idea based on the digital data, I expand the perception of Lítla Dímun.

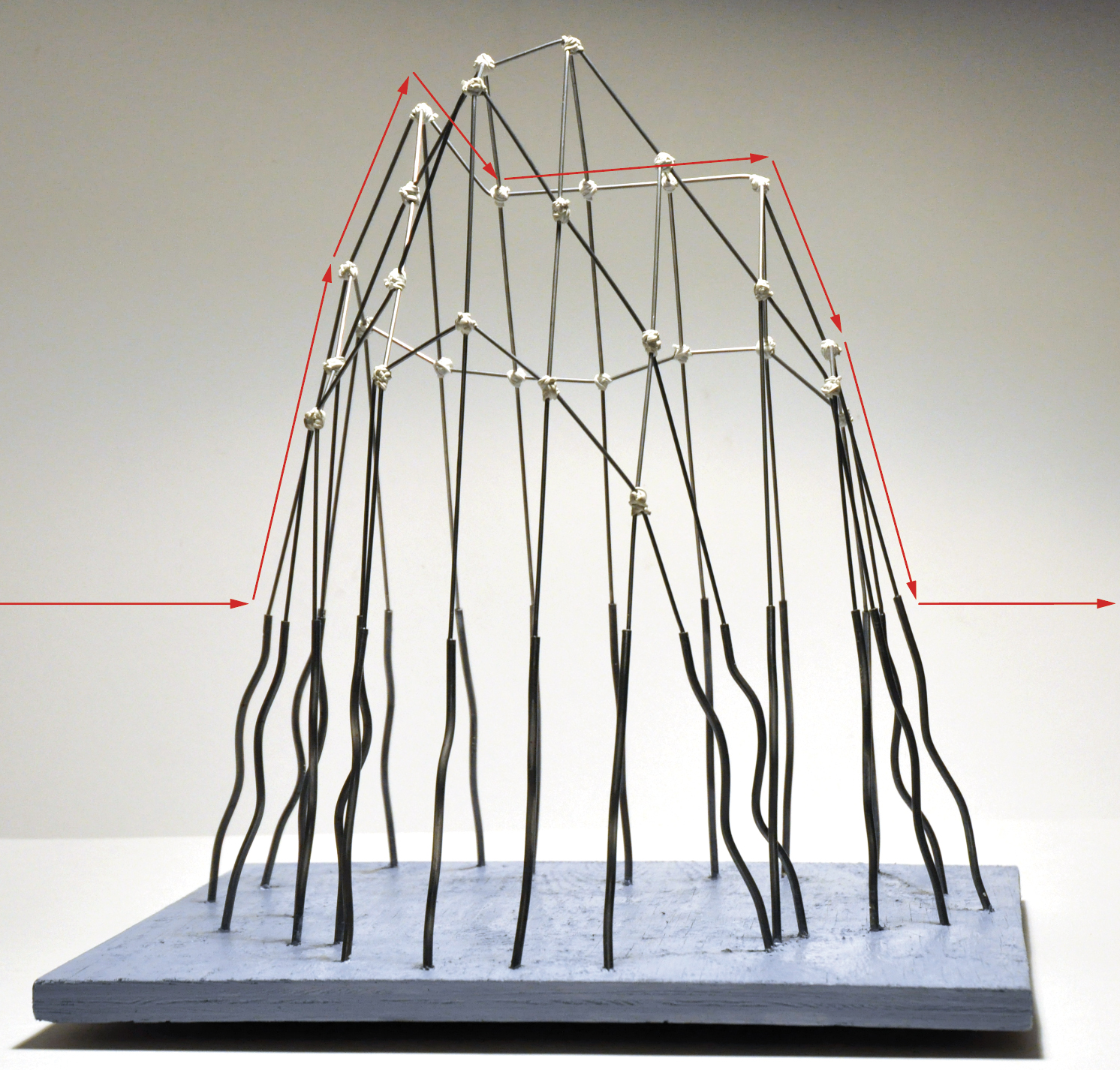

I first construct a 2-mm iron wire model using my 30 datasets to test my theory of a physical representation of the outcrop. The individual data sets indicate where the two meridians must cross and at what height. I raise the model of the shape of the island on 24 thicker threads that continue the direction of the lower parts of the model with an elongated sine curve that imitates the wave shape of the sea. This will be the base of the sculpture.

9

9I enlarge the model to a height of four meters and place it in the art museum in the archipelago’s capital, Tórshavn. Now the public can experience this representation of the island of Lítla Dímun, which in its proper form is 414 meters high and lies 43 kilometers south of the museum. The representation is now presented as a work of art and offers new ideas about the island. The work interacts with the Faroese expression ,”í Dímun” (in Dímun) when you are on the island. With this sculptural representation, one can now physically place people inside the island - “í Dímun”.

10

10In time, wind, sea, and gravity will defeat the rock’s stubborn resistance and the island’s body will dissolve into the depths, for the fierce turbulence of the sea is constant, violent, and tireless. I have to admit that the island is being transformed slowly. The solid vertical cliff foot is worn away by the rapidly changing waves. The only thing that separates the island and the water when their surface shape is to be measured is the great difference in the time factors under which they change. If the measurement density in time can be made sufficiently short, the rock and the sea appear with the same firmness. But the measurement is only correct in this short period of time. Therefore, any record and subsequent representation of the shape of the island is essentially obsolete.

11

11As the masses of water flow over the seabed and squeeze between the landmasses, human bodies squeeze across the surface of the island and find passage on surfaces and slopes, between peaks and hills, and through valleys. Surface scans with the body were humans’ first method of recognising the surfaces and shape of the land. This is a method without considerations, where the body is brought into direct contact with its environment through the perception of the senses and tactile interaction. No theories, no instruments, no representative data systems, only immediate being on the surface.

Every theory, every representation, every system of cognition always puts a distance between the human body and the world. The anchor point that makes it possible to manoeuver between the many theoretical systems of cognition that float in an intangible cloud around the island is the direct location of the body on the island’s surface.

1 – Lítla Dímun, Faroe Islands, August 2019 (Joshua Nash)

2 – Store og Lille Dimon. (Landtoninger fra Færøerne. Krydseren Heimdal (Beskytteren) 1898.

3 – A plane table on Sandoy above Skálhøvdið. Measuring table sheet of Lítla Dímun measured in the period 8 June to 15 June 1899 by the Generalstaben

4 – Map of the Færöerne (The Færöes) from The Danish Government Survey 1895-99, Copenhagen 1900, 41x30 cm, 1900.

5 – The Royal Library. Overview map of the Faroe Islands' measuring table sheets. Mapping of the Faroe Islands. Munksgaard 1944.

6 – Lítla Dímun projected on a map (Ole Wich 2009)

7 – Lítla Dímun. Aerial photo 1958 (Umhvørvisstovan - www.us.fo)

8 – Screenshot from https://kort.foroyakort.fo/kort

9 – 3D Dímun. Listasavn Føroya (Ole Wich)

10 – Model of 3D Dímun, 2009 (Ole Wich)

11 – Body at Byrgisstakkur on Hestur (Ole Wich)